The Welsh Government presented the long-awaited Disused Mine and Quarry Tips (Wales) Bill to the Senedd in December 2024. Read our policy brief on what it needs on-page.

Coal tips, also known as coal spoil or slag heaps, and overburden are large mounds of waste soil, rocks, and fragments of coal that was dumped there as it was originally in the way between a mining company and the profitable coal it wanted to mine. Sometimes, mining companies promised to return these coal tips down the holes or into the voids they created, but often claimed bankruptcy or found loopholes to avoid this costly process. There are over 2,500 coal tips peppering Wales alone.

The coal tip slip in the town of Cwmtillery on Sunday 24th November 2024 occurred during Storm Bert, which brought intense rainfall. The coal tip is Category D, which means it is monitored every 6 months – and the last report did not flag any major issues. It follows on from the coal tip slip in 2020, which sent 60,000 tonnes of soil and rocks tumbling in Tylorstown, Rhondda Cynon Taf. That compares with 40,000 tonnes of debris that were dislodged and tumbled into a school in the infamous Aberfan disaster of 1966. Unlike the Aberfan tragedy, the two recent coal tip slips luckily resulted in no loss of human life.

What each of these coal tips have in common is that they occurred after a period of heavy rain. Leader of Blaenau Gwent council Steve Thomas commented on the recent coal tip slip in Cwmtillery, saying "We can confirm that we are dealing with a localised landslide believed to be caused by excess water as a consequence of weather experienced during Storm Bert."

Geologist Dr Jamie Price explained: "Both more prolonged and more intense rainfall events will heighten the risk of coal tip collapses….Increases in the moisture content of the coal tips and increases in groundwater level in general can affect the stability of these coal tips and could induce failure and collapsing of the coal tips."

A Cabinet Statement by the Welsh Government in 2023 stated “Winter rainfall has increased in Wales in recent decades, and the Met Office predicts that it will increase further as a result of global warming.”. By 2050 it's thought it could get 6% more rainy in winter in Wales, with as much as 13% more rain by the 2080s. Human-induced climate change made the heavy storm downpours and total rainfall across the UK and Ireland between October 2023 and March 2024 more frequent and intense, according to a rapid attribution analysis by an international team of leading climate scientists. This is exactly what we recently experienced with Storm Bert which led to the most recent coal tip slip in Cwmtillery.

ERI Ltd is a mining company that’s seized on community fears in Bedwas, South Wales, to propose mining two of coal tips in the area of around 500,000 tonnes of ‘waste’ coal contained within them on the promise of levelling out the coal tips afterwards. ERI Ltd is tempting Caerphilly County Council with the offer to do this at no cost to the Council, claiming it’ll use a portion of the profits gained by selling the coal it removes from the tips. The problem with this approach is:

Karadeniz kıyısında ağaçlarla kaplı dağların arasında yer alan küçük Ereğli şehri, Erdemir çelik fabrikasının gölgesinde kalıyor. Bu fabrika, kömür kullanarak çelik üreten Türkiye'deki üç izabe fırın çelik fabrikasından biri ve Ereğli’deki insanların hayatını ve sağlığını doğrudan etkiliyor.

Yerel halkın evleri, her birkaç dakikada bir buhar bulutları yayan ve körfezin karşısındaki apartmanları gizleyen bu devasa çelik fabrikasının etrafında bir amfitiyatro gibi konumlanıyor. Coal Action Network (Kömür Eylem Ağı) araştırmacıları, Cumbria’da yeni bir kömür madeninin açılması ve Türkiye’ye kömür sağlaması ihtimali doğunca, Erdemir çelik fabrikası gibi kömür yakan tesislerden etkilenen insanlarla görüşmek için Türkiye’ye geldi.

Coal Action Network’ün Türkiye’yi neden ziyaret ettiği ve Birleşik Krallık’taki kömür madenciliği bağlantıları hakkında daha fazla bilgi için bu sayfayı ziyaret edin.

Türkiye, çelik fabrikaları ve elektrik santrallerinde ithal kömür kullanıyor ve aynı zamanda yerli kömür de çıkarıyor.

Türkiye, küresel olarak sekizinci en büyük çelik üreticisi. 2023 yılında, 33,7 milyon ton çelik üretti ve 21,1 milyon ton hurda metal tüketti. Ülkedeki 30 çelik fabrikasından 27’si elektrik ark fırınlarında hurda metalleri eriterek çelik üretiyor ve ülkenin çelik üretiminin %72’sini sağlıyor. Çelik üretim sürecinde kok kömürüne dönüştürülmüş kömür kullanılan üç izabe fırın ve ısı sağlamak için kömür kullanan birçok elektrik ark fırınları bulunuyor. Bu kömür büyük ölçüde ithal ediliyor. Rusya, Türkiye'nin kömür ithalatının %73'ünü sağlıyor, kalan kısmının çoğu ise Kolombiya’dan geliyor.

Elektrik ark fırınları büyük miktarda elektrik tüketiyor ve Türkiye'de bu elektriğin büyük bir kısmı elektrik şebekesi üzerinden kömürden sağlanıyor. Türkiye’de bir elektrik ark ocağı, kendi kömürlü elektrik santraline sahip. Türkiye'nin elektriğinin %35’i kömürden sağlanıyor (2022 yılı verisi). Türkiye, 2023 yılında 18 milyon ton çelik ithal etti ve 12,7 milyon ton çelik ihraç etti. Şu anda hurda metal eritmek için kömür kullanan 20’den fazla elektrik ark fırını çelik tesisi var. Çelik, Türkiye'nin üçüncü en büyük ihracat sektörü.

Türkiye, Rus kömürünün en büyük beş ithalatçısından biri. Birçok ülke, 2022'de Ukrayna’nın işgalini takiben, yaptırımlar kapsamında Rus kömürü almayı durdurdu. Bunlar arasında Birleşik Krallık, AB üyesi ülkeler ve ABD de bulunuyor.

Enerji ve Temiz Hava Araştırma Merkezi’nden (CREA) Vaibhav Raghunandan, "Türkiye'nin artan Rus kömürü bağımlılığı (ve diğer fosil yakıtlar) giderek daha değişken hale gelen bir tedarikçiye bağımlı olması anlamına geliyor. Rus kömür sektörü Kremlin için büyük bir gelir kaynağı ve Rusya Enerji Bakanlığı, 2035 yılına kadar küresel kömür pazarının %25’ini elde etme hedefi koydu. Kömürden elde edilen vergiler, Federal Bütçe’nin önemli bir parçasını oluşturuyor. İşgalden bu yana Türkiye – bir NATO ülkesi – Rus kömürü için 8,2 milyar avro ödedi, bu da Rusya'nın Ukrayna'yı işgalini etkili bir şekilde finanse ediyor" dedi.

İşgalden sonra Türkiye, Rus kömüründeki pazar payını artırdı. Türkiye’nin ithalatı, Rusya’nın toplam kömür ihracatının %13’ünü oluşturuyor. 2024’ün ilk üç çeyreğinde Türkiye, 15,7 milyon ton Rus kömürü ithal etti; bu da Türkiye’nin toplam kömür ithalatının %49’unu oluşturuyor (değeri 1,66 milyar avro). Bu, işgal öncesi dönemin aynı dönemine kıyasla %82’lik bir artış anlamına geliyor.

Ayrıca, Rus kömür madenciliği sektörü kültürel soykırım, çevresel yıkım ve hava kirliliği sorunlarına neden oluyor. Bu konular, Coal Action Network ve Fern'in "Sibirya'da Yavaş Ölüm" adlı raporunda ayrıntılı olarak ele alınıyor.

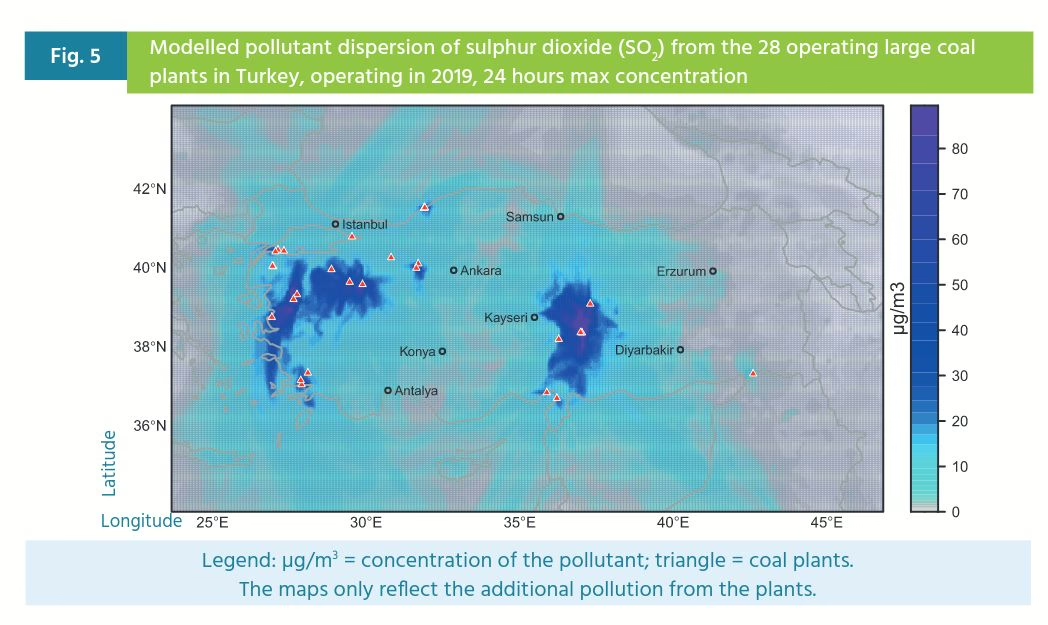

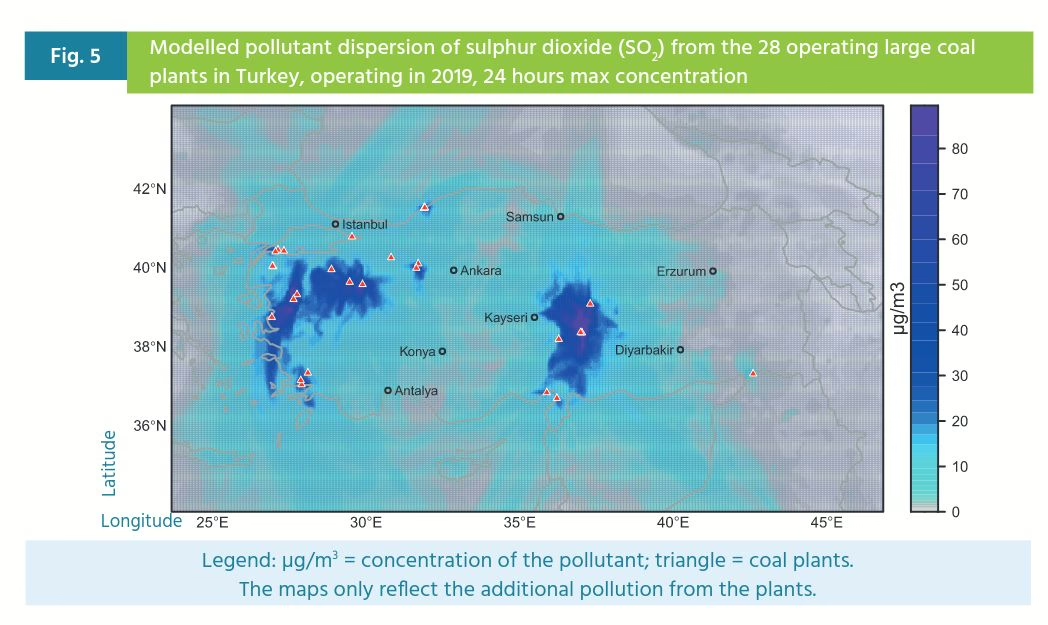

Dünya Sağlık Örgütü'ne göre, hava kirliliği, dünya genelinde ve Türkiye’de halk sağlığı için en büyük çevresel tehdit. Çelik fabrikalarından ve elektrik santrallerinden kömür tüketimi sırasında salınan sağlığa zararlı dört ana kirletici bulunuyor: Sülfür dioksit (SO2); partikül madde – PM10 ve daha küçük PM2.5; azot oksitler (NOX) ve cıva.

Yüksek sülfür içerikli kömürün yanmasıyla oluşan SO2 solunduğunda, felç, kalp hastalığı, astım, akciğer kanseri ve ölüm gibi sağlık sorunları riskini artırıyor. Solunması son derece toksik olarak sınıflandırılıyor. Yüksek konsantrasyona bir kez bile maruz kalma, astım gibi kalıcı bir duruma yol açabilir. Türkiye’de SO2 emisyonları 2019 yılında %14 artış göstererek, emisyonların arttığı nadir ülkelerden biri oldu. Türkiye’de kömür bazlı enerji üretimi, SO2 emisyonlarının en büyük kaynağı olmaya devam ediyor.

Ereğli’de, Erdemir çelik fabrikasının çevresinde yaşayan halk, sağlıklarına ilişkin üniversitelerin yaptıkları çalışmaların genellikle hükümet tarafından ört bas edildiğini söyledi. Ancak Ereğli'deki multipl skleroz (MS) oranlarını, 40 km uzakta temiz bir kent olan Devrek ile karşılaştıran bir çalışma, “bir demir çelik fabrikasının bulunduğu bölgedeki [Ereğli] MS prevalans oranının kırsal bir şehirle [Devrek] karşılaştırıldığında iki kattan fazla olduğunu” gösteriyor. Bu da hava kirliliğinin MS hastalığının olası bir nedeni olabileceği hipotezini destekliyor. Yerel halk, çelik fabrikasının havayı kirlettiği ve sağlıklarını bozduğu konusunda ikna olmuş durumda.

Karadeniz, Ereğli ve Alaplı Çevre Gönüllüleri lideri Çetin Yılmaz, Erdemir’de yaşanan sorunları tartışmak üzere Coal Action Network ile görüşmek isteyen 15 endişeli vatandaşı bir araya getirdi. Bu kişiler, çelik fabrikaları ile yerel halkın sağlığının bozulması arasında bağlantılar olduğunu gösteren ancak hükümet tarafından gizlenen bilimsel çalışmalardan yakınıyorlar.

Çetin, “Şirket [Eren Energy] birçok insanda kansere neden oldu, çalışanlarının sendikalaşma hakkını tanımıyor; sendikalaşmak isteyen işçileri işten çıkardı; Çatalağzı’nı nefes alınamaz bir hale getirdi; balık üreme alanlarını külle doldurdu; yılda 2 milyon ton ithal kömür yakıyor ve bölgemizde insanlara ve doğaya en büyük zararı veriyor” diyor.

Erdemir çelik fabrikasında 18 yıldır çalışan bir işçi, gırtlak kanseri olduğunu anlatırken bu sesinden duyulabiliyordu. Yerel halkın %50’sinin sağlığının çelik fabrikasından etkilendiğini düşünüyorlar. Bir öğretmen, her sınıfında yaklaşık 10 çocuğun kötü hava kalitesi nedeniyle solunum sorunları yaşadığını anlattı.

Yerel siyasi temsilci Coal Action Network’e, “Buradaki çoğu kişi madenlerde veya çelik fabrikasında çalışıyor, herkes hava kirliliğinin kansere ve solunum zorluklarına neden olduğunu biliyor. Çalışanlar bu konuda bir şey yapacak durumda değil çünkü para kazanmaları gerekiyor ve işlerini kaybetme tehlikesi yaşıyorlar” dedi.

Erdemir ve İsdemir izabe fırınlarının sahibi olan OYAK, karbonsuzlaşmak için yedi farklı yöntem kullanacağını belirtiyor. Ancak sözde Net Sıfır Yol Haritası, emisyonları azaltma amaçlı potansiyel seçeneklerin bir listesi gibi duruyor; gerçek bir plan barındırmaktan oldukça uzak.

İsdemir’deki hava kirliliği ve sağlık sorunlarının Erdemir’deki durumla benzer olması muhtemel. Türkiye’nin izabe fırın çelik üretimindeki CO2 yoğunluğu, Avrupa, ABD ve Güney Kore’de üretilen çeliğin emisyonları ile kıyaslandığında daha yüksek düzeyde.

Türkiye'deki çelik üretim değer zincirinde çevre, kamu ve iş sağlığı düzenlemelerine uyum konusunda uzun süredir aksaklıklar yaşanıyor.

Avrupa’nın doğu sınırında yer alan Türkiye’nin, 2024'te Avrupa’nın en büyük kömürle çalışan elektrik üreticisi olan Almanya’yı geride bırakması bekleniyor. Türkiye, 2022 yılında açılan Hunutlu Termik Santrali gibi yeni kömürlü termik santralleri açmaya devam ediyor. Türkiye’de 34 kömürlü termik santral var; bunlardan 10'u taş kömürü kullanırken geri kalanı daha düşük enerji yoğunluğuna sahip, daha düşük kaliteli linyit kömürünü kullanıyor. Kömürle çalışan iki izabe fırının ayrıca elektrik sağlayan kömür santralleri de bulunuyor.

Türkiye'nin elektrik tüketimi son yirmi yılda üç katına çıktı; bu artış büyük ölçüde kömür ve gaz üretimindeki hızlı büyümeye dayanıyor.

Ereğli’nin yanı sıra, Coal Action Network, Zonguldak ilçesinde Muslu yakınlarındaki ZETES III ve IV ile Çatalağzı isimli üç kömürlü elektrik santralini ziyaret etti.

Zonguldak, 2020 yılında covid-19 önlemleri kapsamında Türkiye genelinde hafta sonu sokağa çıkma yasaklarına büyük şehirlere ek olarak dahil edilen tek bölgeydi. Bu karar, düşük hava kalitesine bağlı olarak önceden yüksek oranlarda görülen kronik solunum yolu hastalıkları nedeniyle alındı. Yerel yetkililere göre, bölge nüfusunun yaklaşık %60’ının belirli bir dereceye kadar solunum semptomları gösterdiği tahmin ediliyor ve 2010 ile 2020 arasında ölüm oranları neredeyse iki katına çıkmış durumda. Düşük hava kalitesi, çelik fabrikaları, kömür madenleri ve taş kömürü santrallerinden yayılan yüksek düzeydeki PM2.5 ve SO2 kirleticilerinden kaynaklanıyor.

Türkiye’de sadece kömürden elektrik üretiminin sağlık maliyetleri, 26,07 - 53,60 milyar Türk Lirası (2,86 - 5,88 milyar €) arasında olup, bu tutar Türkiye’nin yıllık sağlık harcamalarının %13 - %27’sine eşit.

Türkiye'nin çelik fabrikaları ve elektrik santralleri ile ilgili olarak AB’nin geri kalanından önemli ölçüde ayrıldığı nokta, hava kalitesi standartlarına uyum ve bu standartların uygulanması. “AB üye ülkeleri, tesis düzeyindeki emisyonları kamuya açık bir veri tabanına bildirmekle yasal olarak yükümlüyken [...] Türkiye elektrik santrali veya sektörel emisyon verilerini paylaşmıyor. Bunun yerine, elektrik üretimi ve ısıtma sektörüne ait birleşik verileri raporluyor.” Bu durum verileri gizliyor. Ayrıca Türkiye, sülfür emisyonlarını sınırlama ve diğer kirleticilerle ilgili iş birliği yapma amacı taşıyan üç önemli teknik anlaşmayı imzalamadı. Bunlar; Sülfür Emisyonlarının Azaltılması üzerine 1985 Helsinki Protokolü, Sülfür Emisyonlarının Daha Fazla Azaltılması üzerine 1994 Oslo Protokolü ve Asitlenme, Ötrofikasyon ve Yüzeyde Ozonu Azaltma üzerine 1999 Göteborg Protokolü’dür. HEAL, “Şeffaflık eksikliği, ülkede hava kalitesini ve sağlığı iyileştirme konusunda rasyonel ve bilgiye dayalı bir tartışmayı engelliyor” diye belirtiyor. Yerel halk ve ekosistemler, sonuçlarıyla baş başa kalıyor.

Son yirmi yılda Türkiye’de özelleştirilen elektrik santrallerinin birçoğu SOx filtre teknolojisini kullanmıyor ve bunlar Türkiye’nin artan SOx kirliliğine başlıca katkı sunanlardan.

Coal Action Network ile görüşen herkes, Türkiye’nin kömür tüketen tesislerinin hava kalitesi üzerindeki etkileri hakkında endişe duyuyor. Karadeniz yakınlarında, Zonguldak’ta üç kömürlü termik santraline yakın yaşayan bir sakin, “İnsanlar belirli dönemlerde santrallerdeki hava kirliliği filtrelerinin düzgün çalışmadığına inanıyor. Yılda 250 gün boyunca kirlilik, hükümetin kabul edilebilir standartlarının üzerinde oluyor” diyor.

Çelik fabrikalarını veya kömürlü termik santralleri ile yaşayan yerel sakinlerin genel anlatımı, kötü hava kalitesi, daha yüksek oranlarda solunum hastalıkları, çeşitli kanser türleri ve bitki ve bitki örtüsünün ölümü sonucunda yerel halkın yiyecek yetiştirememesi yönündeydi.

2021’de Türkiye, elektrik santralleri ve çelik fabrikaları için 36 milyon ton kömür ithal etti ve çoğunlukla çelik yapımında kullanılmayan yerli linyit kömürünü de tüketti. Türkiye Kömür İşletmeleri, kömür ithalatındaki en büyük artışın elektrik üretim talebinden kaynaklanacağını vurguluyor ve bu eğilimin devam edeceğini öngörüyor. Cumhurbaşkan Erdoğan, ülkenin 2053’e kadar karbonsuzlaşacağını söylüyor, ancak izabe fırınları karbon azaltım stratejilerine dahil etmeye yönelik anlamlı bir yol haritası bulunmuyor.

Ekosfer'den Barış Eceçelik, “Türkiye, Avrupa'da kömürü aşamalı olarak kaldırmak için bir tarih belirlememiş birkaç ülkeden biri. Geçen yıl, Türkiye tarihinde ilk kez, ithal kömür elektrik üretiminde en önde gelen enerji kaynağı haline geldi. Türkiye, rüzgar, güneş ve biyokütle dahil olmak üzere yenilenebilir enerji kaynakları için önemli bir potansiyele sahip. Ancak ciddi bir iklim hedefinin ve kömür kullanımına karşı önlemlerin olmaması hava kirliliğine ve yüksek düzeyde enerji bağımlılığına yol açtı. İthal kömür, iklim değişikliği veya hava kirliliği sorunlarına bir çözüm değil” diyor.

Kömürlü termik santrallerinin çevresindeki kirlilik sorunları sadece hava kalitesini etkilemekle kalmıyor. Aynı zamanda Karadeniz üzerinde büyük bir etkiye sahip. Elektrik santrallerinde soğutma işlemlerinde kullanılan suyun daha sonra denize geri verilmesi nedeniyle, santralin çevresindeki suyun diğer yerlere kıyasla 4 derece daha sıcak olduğu bildiriliyor. Yerel halk, santrallerden salınan ağır metaller ve diğer toksinlerden kaynaklanan bir tabakanın su yüzeyinde görüldüğünü bildiriyor. Yüksek sülfür içeriğine sahip kömürün yakılması, asit yağmuru üreterek göl ve akarsuları asitleştiriyor. Karadenizli balıkçılar, santrallerin balık üreme alanlarına zarar verdiğini ve yakaladıkları balık miktarını azalttığını belirtiyor. Bu balıklar İstanbul ve Ankara’ya satılıyor.

Kömür, Türkiye’de tartışmalı bir konu. Mevcut kömür tesislerine yakın yaşayan insanlar güvenli iş imkanları isterken, yeni madenlere karşı protestolar da var. 2013 yılında bir linyit kömür madeninin önerilen açılışı protestoların ardından iptal edildi. Maden kazaları ise oldukça yaygın; 2022 Ekim ayında Karadeniz yakınlarında derin bir madende 41 kişi öldü ve 11 kişi ağır yaralandı.

Kokurdan (resmi adı: Körpeoğlu) adlı yüksek dağ köyünde, kömür külü ve atık döküm alanı, yerleşim havuzunun çevresindeki yoğun ağaçlara toz bulutları saçıyor. ZETES elektrik santrallerinin külü ve hava filtrelerinden çıkan kirletici maddeler açık bir alanda biriktiriliyor. Coal Action Network, köyü, bitki örtüsünün, evlerin ve yolların yoğun bir yağıştan sonra tozdan temizlendiği bir zamanda ziyaret etti; ancak ZETES kömürlü termik santrallerinden gelen atıklar, bu insanların ciğerlerinde, evlerinde ve ekinlerinde birikiyor.

Köylüler, Coal Action Network’e, kömür tesislerinin bu tür kirlenmelere neden olduğu bir bölgeyi neden ziyaret etmek istediğimizi sordu. Yolda geçerken bir kadın, “Buradan nefret ediyorum, çünkü burası kirlilik nedeniyle yaşanmaz halde. Hava kuru olduğunda toz her şeyi kaplıyor” dedi. Bu köyde insanlar, iş imkanları yüzünden verilen zararın buna değdiğine ikna olmuyor. Yerel halk kömürlü termik santralleri hakkında iyi bir şey söylemiyor; yalnızca sağlık üzerindeki olumsuz etkilerden, ayrıca karaciğer kanseri ve mide kanseri gibi hastalıklardan bahsediyor.

En temel hava kirliliği kontrolleri bile uygulanmıyor – kömür taşıyan kamyonlar, tozun güzergâh boyunca yayılmasını önlemek için kapatılmıyor; bu önlem uzun zaman önce Birleşik Krallık'ta standart hale gelmişti. ZETES elektrik santrallerinin konveyör bantlarının altından kamuya açık yollar geçiyor.

PM10 olarak bilinen ince toz partiküllerini izleme cihazları çelik fabrikalarının çevresinde çalışmıyor. PM2.5, akciğerlere nüfuz edebilen ve hatta kan dolaşımına girerek astım, kalp krizi ve bronşit gibi kronik hastalıklara yol açabilen daha ince bir partikül. Ereğli çevresinde PM2.5 ölçümü yapılmıyor.

Coal Action Network’ün Karadeniz kıyısında dört kömür tesisini ziyaretinde, kömür yakmanın insan ve çevre üzerindeki maliyetlerinin yüksek olduğu görüldü. Sağlık, yerel çevre ve iklim değişikliği sorunları yeterince ele alınmıyor, ancak kömür tesislerine yakın yaşayan topluluklar bu durumun iyileştirilmesini talep ediyor.

Last December in London, the CAN team protested with other climate campaigners for two days in freezing temperatures outside one of the world’s biggest events funnelling investment into expanding mining globally. The ‘Mines and Money Conference’ held in London’s Business Design Centre connected investors with projects and companies responsible for human rights abuses, ecocide, and fuelling climate chaos.

Send an email to pressure the Business Design Centre to live up to its ‘B Corp’ ethical status by dropping the ‘Mines and Money Conference’ this December. We’ll send your email to a list of over 60 other B Corp certified big players, suggesting they protect the reputation of B Corps that they themselves rely on. Pressure from these big players might just be enough to get the Business Design Centre to drop the Mines and Money Conference to save its B Corp status.

Coal Action Network has been campaigning for a ban on new coal mining for years, and met with numerous MPs in the lead-up to the 2024 UK General Election. Together with our supporters, we celebrate this clear win for us and for all the communities that won't now suffer noise, dust, and traffic pollution from nearby coal mining. As the first G7 country to ban coal mining, it also sets an example to other G7 countries to follow.

The UK Government has laid a Written Ministerial Statement confirming that it will introduce legislation to "restrict the future licensing of new coal mines", by amending the Coal Industry Act 1994, "when Parliamentary time allows".

The UK Government's press release is entitled "New coal mining licences will be banned". We thinks it's great that the UK Government is following through on its historic manifesto pledge to rule out new coal mining throughout the UK. Following on the coattails of the UK’s exit from coal-fired power generation, this commitment bolsters the UK’s international reputation in leaving behind the world’s dirtiest fossil fuel. We hope to work with the UK Government to ensure no loopholes are carried into the final wording, and to leverage similar commitments in other G20 countries

Türkçe için bu web sayfasına bakın.

The small city of Ereğli nestles between tree covered mountains and Turkey’s Black Sea coast. The city is dominated by the Erdemir steelworks. It is one of three blast furnace steelworks in Turkey, using coal to produce steel. Erdemir is a mighty presence in the lives and lungs of the people living nearby.

Local people’s homes sit in an amphitheatre surrounding the vast steelworks, which sends plumes of steam into the air every few minutes that shimmers and obscures apartment blocks across the bay. Investigators from Coal Action Network travelled to Turkey to speak with people currently affected by Turkish coal burning facilities, like the Erdemir steelworks, when it looked possible that a new coal mine would open in Cumbria and supply coal to Turkey, perpetuating the local populations’ air pollution issues. For more information on why Coal Action Network visited Turkey and links to UK coal mining, see this page.

Turkey uses imported coal in its steelworks and power stations, as well as mining domestically.

Turkey is the 8th biggest steel producer globally. In 2023, it produced a massive 33.7 million tonnes of steel and consumed 21.1 million tonnes of scrap metal, according to World Steel Association. 27 of the 30 steelworks in the country produced steel by melting down scrap metal produced in Electric Arc Furnaces (EAF), producing 72% of the country’s steel output. There are three blast furnaces that use coal, converted into coke, in the steel making process, and many of the EAFs use coal to provide heat. This coal is largely imported. Russia supplies 73% of Turkey’s coal imports, and Colombia the bulk of the remainder.

EAFs consume large amounts of electricity. In Turkey, much of this electricity comes from coal through the power grid. One Turkish EAF has its own coal power station. Coal power supplied 35% of Turkey’s electricity in 2022. Turkey both imports and exports large quantities of steel (18 million tonnes and 12.7 million tonnes respectively, in 2023). More than 20 of the EAF steel facilities currently use coal to melt scrap metal. Steel is the country’s third largest export sector.

Turkey is one of the top five importers of Russian coal. Many countries, including the UK, EU member states and USA stopped buying Russian coal, as part of sanctions following the country’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Vaibhav Raghunandan, from Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) says, “Turkeyʼs increased reliance on Russian coal (and indeed other fossil fuels) is effectively tying it down to an increasingly volatile supplier who controls their market. The Russian coal sector is a huge source of revenue for the Kremlin and the Energy Ministry had set targets of attaining 25% of the global coal market by 2035. Taxes from coal constitute a significant part of the Federal Budget. Since the invasion, Turkey — A NATO country — has paid EUR 8.2 bn for Russian coal, which effectively finances Russiaʼs invasion of Ukraine.”

Since the invasion Turkey has increased its market share of Russian coal, Turkey’s imports constitute 13% of Russiaʼs total coal exports. In the first three quarters of 2024, Turkey has imported 15.7 million tonnes of Russian coal, making up 49% of Turkey’s total coal imports (valued at EUR 1.66 billion). This is an 82% increase when compared to the same period in the year prior to the invasion.

Additionally, the Russian coal mining industry causes cultural genocide, environmental destruction and air pollution issues, detailed in Coal Action Network and Fern’s report, Slow Death in Siberia.

According to the World Health Organization, air pollution is the largest environmental threat to people’s health across the globe, including in Turkey. There are four main health harming pollutants released in coal consumption from steelworks and power stations: Sulphur dioxide (SO2); particulate matter – PM10 and the smaller PM2.5; nitrogen oxides (NOX) and mercury.

Breathing SO2, which is produced on combustion of high sulphur coal, increases the risk of health conditions – including stroke, heart disease, asthma, lung cancer and death. It is classified as very toxic when inhaled. Even a single exposure to a high concentration can cause a long-lasting condition like asthma. SO2 emissions rose by 14% in Turkey in 2019, one of the few countries in which emissions increased in that year. Coal-based energy production remains the major source of SO2 emissions in Turkey.

Local people in Ereğli, the city surrounding the Erdemir blast furnace steelworks, told Coal Action Network that university studies into their health are normally suppressed by government. However, in a study looking at the incidence of multiple sclerosis (MS) in populations in Ereğli compared to Devrek, which is a rural and clean city located 40 km away from Ereğli, “indicate a more than double MS prevalence rate in the area home to an iron and steel factory [Ereğli] when compared to the rural city [Devrek]. This supports the hypothesis that air pollution may be a possible etiological [Pertaining to, or inquiring into, causes] factor in MS.” Local people take no persuading that the air is contaminated by the steelworks and damaging their health.

Çetin Yılmaz, leader of Black Sea, Ereğli and Alaplı Environmental Volunteers, brought together 15 concerned citizens from Erdemir to talk with Coal Action Network about the impacts they face in the town surrounding the steelworks. They bemoan the scientific studies which show links between the steelworks and the diminishing health of the local population, but which are suppressed by the Government.

Çetin says, “The company [Eren Energy] has caused cancer in many people, it does not recognize the right of their employees to unionize in its facilities; it has fired workers who want to be unionized; it has made Çatalagzı into a breathless state; it has filled fish breeding grounds with ash; it burns 2 million tons of imported coal every year and caused the greatest damage to humans and nature in our region.”

A worker, who has worked at the Erdemir steelworks for 18 years, explained how he got throat cancer, which could be heard affecting his voice when we met him. Local people think 50% of the population’s health is affected by the steelworks. A teacher present recalled how in each of his classes around 10 children will have breathing issues, caused by the poor quality air.

The local political representative told Coal Action Network, “Most people here work in mines or in the steel plant, everyone knows that the air pollution causes cancer and breathing difficulties. The workers aren’t in a position to do anything about it as they have to earn money and would lose their employment, as well as their health.”

OYAK, the company which owns Erdemir and İsdemir blast furnaces, says it will use seven different methods to decarbonise. Its so called Net Zero Roadmap reads more like a list of potential options to reduce emissions and does nothing to resemble an actual plan.

Air pollution and health problems at İsdemir are likely to mimic those at Erdemir. Turkey’s CO2 intensity for the blast furnace steel production exceeds the comparable emissions for steel produced in Europe, the USA, and South Korea.

There have been persistent shortcomings in compliance with environmental, public, and occupational health regulations across the steel production value chain in Turkey.

Sitting at the eastern edge of Europe, Turkey is expected to surpass Germany as Europe's largest coal-fired electricity generator in 2024. Turkey is still opening new coal power stations, such as Hunutlu Thermal Power Plant opened in 2022. Turkey has 34 coal fired power stations, 10 use hard coal and the remainder use lignite, a less energy dense, poorer quality coal that is burnt close to its source. Two of the blast furnaces using coal also have coal power stations providing their electric.

Turkey’s electricity consumption has tripled in the last two decades, which has been underpinned by rapid growth in coal and gas generation.

As well as Ereğli, Coal Action Network visited three coal fired power stations near Muslu, called ZETES III and IV and Çatalağzı. All of the sites are within the district of Zonguldak.

Zonguldak was the only non-metropolitan district included in Turkey-wide weekend curfews for covid-19 reduction measures in 2020. This was due to pre-existing high rates of chronic respiratory diseases caused by poor air quality. According to local officials, it’s estimated that as much as 60% of the population displays some degree of respiratory symptoms, with mortality rates almost doubling between 2010 and 2020. The low air quality is caused by elevated levels of PM2.5 and SO2 pollutants from steelworks, coal mines and hard coal power plants.

The health costs from coal power generation in Turkey alone, are 26.07 - 53.60 billion Turkish Lire (2.86 - 5.88 billion €), which is equivalent to 13 - 27% of Turkey’s annual health expenditure.

Where Turkey significantly deviates from the rest of the EU in relation to steelworks and power stations is in the compliance and enforcement of air quality standards. As a report by Health and Environment Alliance (HEAL) shows, “While EU member states are legally required to report emissions at plant level to a publicly accessible database [...] Turkey does not share power plant or sectoral emission data. Instead, it reports merged data for electricity generation and the heating sector” This obscures the data. Furthermore, Turkey has not signed other important technical agreements to limit, and cooperate on, other pollutants. This includes three protocols on sulphur emissions (The 1985 Helsinki Protocol on the Reduction of Sulphur Emissions, the 1994 Oslo Protocol on Further Reduction of Sulphur Emissions, and the 1999 Gothenburg Protocol to Abate Acidification, Eutrophication and Ground-level ozone.). As HEAL states, “The lack of transparency prevents a rational and informed debate about improving air quality and health in the country.” Local people and ecosystems are left to deal with the consequences.

In the last 20 years, Turkey’s power plants that have been privatised and many do not use filter technology for SOx. They are the major contributor to Turkey’s increasing SOx pollution.

Everyone who spoke to Coal Action Network is worried about the air quality impacts of Turkey’s coal consuming plants. A resident living near three coal power stations on the Black Sea, near Zonguldak, says, “people believe that in some periods the air pollution filters on the plants are not working properly. Habitually, we have 250 days in a year the pollution is higher than the government’s acceptable standards.”

The consistent narrative from the residents overlooking either the steelworks or the coal power stations was one of poor air quality, resulting in higher rates of respiratory illness, cancers of various sorts, and death of plants and vegetation leading to an inability of local people to grow food.

In 2021, Turkey imported 36 million tonnes of coal for its power stations and steelworks, as well as using its domestically mined coal, which is mainly lignite, not used in steel-making. Turkish Coal Enterprises emphasises that the most significant increase in coal imports will come from the demand for electricity generation, and estimates that this trend will continue. Although President Erdoğan says the country will decarbonise by 2053 there is no meaningful road map to bring the blast furnaces into relevant carbon reduction strategies.

Barış Eceçelik from Ekosfer states, “Turkey is one of the few countries in Europe that has not set a date for the phase-out of coal. Last year, for the first time in the history of Turkey, imported coal became the leading energy source in electricity generation. Turkey has significant potential for renewable energy sources, including wind, solar, and biomass. However, the lack of a serious climate target and measures against coal usage has led to air pollution and a high level of energy dependence. It must be acknowledged that imported coal is not a solution to the issues of climate change nor air pollution.”

The pollution issues around the coal power stations do not just affect air quality. They also have a large impact on the Black Sea. The water around the power station is reported to be 4o warmer than elsewhere, as it is used in the power stations cooling processes and then returned warmed to the sea. Local people report seeing a sheen on the water from the heavy metals and other toxins which are released from the power stations. Burning coal high in sulphur increases sulphur dioxide which produces acid rain, and acidifies lakes and streams. Black Sea fishermen say that the power stations are damaging fish spawning grounds and reducing their catch. Food which is sold to Istanbul and Ankara.

Coal is a contested subject in Turkey. While people living close to existing coal facilities want the secure jobs, there are protests against new power stations and a proposed lignite power station was cancelled in 2013, following protests. Mining accidents are fairly common, with 301 killed in just one accident in Soma in 2014.

In the high up mountain village of Kokurdan (official name: Körpeoğlu) a coal ash and waste dump billows clouds of dust onto the dense trees surrounding the settling pool. Ash from the ZETES power stations and the dirt from the air filters are settled in a vast open dump. Although Coal Action Network visited immediately after heavy rain had washed the dust off the vegetation, homes and roads, the waste from ZETES coal power stations normally accumulates in the lungs, homes and crops of these people.

Villagers approached Coal Action Network to ask why we would want to visit their area when the coal facilities cause such contamination. “I hate being from here because of the pollution. When the weather is dry the dust covers everything.” one woman told Coal Action Network, whilst passing on the street in Kokurdan. In this village they are not convinced the damage is worth it because of the jobs. Local people say nothing good about the coal power plants, they just talked about the damaging health effects, adding liver cancer and stomach cancer to the list of illnesses caused by the coal power stations.

The most basic air pollution controls are not being implemented – lorries carrying coal are not even covered to prevent dust spreading along its route, a measure that long ago became standard in the UK. Public roads also run underneath the conveyor belts of ZETES power stations.

Monitors for fine dust particles known as PM10 are apparently not operational around the steelworks. PM2.5, is finer particulate matter that can penetrate the lungs and even enter the bloodstream and cause chronic diseases such as asthma, heart attack and bronchitis. PM2.5 is not monitored at all around Ereğli.

Coal Action Network’s visit to four coal facilities on the Black Sea showed that the human and environmental costs of burning coal are high. The issues of health, local environment and climate change are not being sufficiently addressed, but there is demand for improvement within Turkish communities living close to coal facilities.

The mining company, Merthyr (South Wales) Ltd, is trying to do the residents of Merthyr Tydfil out of tens of millions of pounds worth of restoration at Ffos-y-fran opencast coal mine by massively reducing the restoration it agreed to carry out at the end of 16 years of coal mining. To understand the lasting impacts this would have, and why we must resist it, we've made a guide on the community impacts of two other cut-price restorations in South Wales where the same happened.

Former opencast coal mining sites like East Pit, Margam Parc Slip, Nant Helen, and Selar are all recent examples of under-restored areas carried out on budgets as little as 10% of what the promised restoration would have cost - sometimes even less. Ffos-y-fran looks set to join that list. Restorations are meant to return natural life to the area after coal mining has finished, often with promises of even more natural habitat and life than there was before. But whilst some of these restorations can superficially appear complete if you don't look too closely and you didn't know what it looked like before, the soil is wrecked, habitats are struggling to take hold, and there are often wire fences and safety warnings about the hazards left behind.

Often planning permission is granted for coal mining on the basis that the area will be restored with even better natural habitats and public amenity (access, facilities etc.) than before. Surrounding communities pay the price for the promised restoration with years of noise, dust, and disruption to their daily lives. When that restoration is inevitably denied by profiteering mining companies, communities report:

The UK was one of the first countries in the world to mine coal so industrially. Many of those coal mines were abandoned, not all of which are even mapped - though over two thousand recorded waste dumps (coal tips) in South Wales alone hints at the scale. Opencast coal mining left particularly visible scars on the landscape so the voids left over were meant to be filled in after the coal was extracted. When applying for coal mining permission, coal mining companies would sign contracts binding them to pay glowing nature reserves to be established after the coal was extracted. But most of the time, these companies siphon off the profits and declare bankruptcy, or find legal loopholes, to dodge their responsibilities to restore the mess they created.

Fortunately, Councils usually require that a small amount is paid to them by the coal mining company either at the start of a coal mine or as it progresses. But this is often around just 10% of the cost of restoring an opencast coal mine. So when the coal mining companies wriggle out of their contractual duty to clean up the mess they created, the Councils are often forced to then pay these same companies these small amounts of money to do basic works to make the site at least safer and less of an eye-sore for the communities living around it - but at 10%, that money doesn't go far, and can't erase the injustice of broken promises to those communities who also paid in years of coal mining, noise, dust, and disruption. Read our flagship report tracking restoration an seven recent sites across South Wales.

To restore the site of a sprawling opencast coal mine can cost over £100 million. The original Ffos-y-fran restoration scheme is estimated to cost £75-125 million. Merthyr Tydfil Council got £15 million from the coal mining company, Merthyr (South Wales) Ltd in 2019, after taking the company to court. Merthyr (South Wales) Ltd is now refusing to fund the restoration it agreed to, despite posting record profits and selling an extra c640,000 tonnes of coal than it was permitted to.

Despite the injustice of it, the £15 million held by Merthyr Tydfil Council's will theoretically go further if it's paid to Merthyr (South Wales) Ltd to carry out a cut-price restoration compared to a new company, as Merthyr (South Wales) Ltd still has a small amount of its machinery and employees on site from when it was coal mining. The same happened when Celtic Energy Ltd refused to fund the promised restoration of four coal mines it operated in South Wales, stealing £millions from local communities and paying their Directors huge bonuses that year. Each Council paid the what little in restoration funds they held to Celtic Energy Ltd to carry out cut-price restorations at each site, leaving a legacy of bitterness in local communities that's alive today.

Budget restorations typically cut corners in the following areas:

The scientific consensus is that we need to decarbonise heavy industry. Steelworks are amongst the worst carbon emitters. Both of the UK steelworks using coal have agreed to convert to electric arc furnaces, a process which sadly requires far fewer steelworkers. When Port Talbot stopped its coal consuming blast furnaces at the end of September there was a poor deal for the workers. British Steel and the government must do better for the workers at Scunthorpe’s steelworks, expected to turn off the blast furnaces by the end of the year.

Former steelworker, Pat Carr, spoke to Anne Harris from Coal Action Network about the financial support offered to workers when the Consett steelworks closed in 1980, and they discussed what can be done better, in workplaces like Scunthorpe steelworks.

Read the full article, in the Canary Magazine from this link

The proposed West Cumbria Coal mine lost its planning permission in September 2024. Since then, its application to get a full coal mining license was refused by the Coal Authority, another nail in the coffin of the proposed coking coal mine.

The Coal Authority use a narrow (and outdated) check list to approve full coal mining licenses.

The Recommendation report from the Coal Authority for this application rejects the application for a full mining license for failing to satisfy both condition 2 and 3, of the above list.

The Coal Authority was unable to verify West Cumbria Mining Ltd's claims of low subsidence risk as West Cumbria Mining Ltd refused to give its modelling parameters to the Coal Authority, citing confidentiality.

Concurrently, the Coal Authority was not satisfied that West Cumbria Mining Ltd is able to finance the project and discharge liabilities especially now that the planning permission has been overturned.

Additionally, the deadline has passed for West Cumbria Mining Ltd to appeal the decision made by the Judge, Mr Justice Holgate, overturning the planning permission granted by the Conservative Government in December 2022. Friends of the Earth’s legal team has had confirmation that no appeal was received before the deadline, meaning an appeal won’t go ahead.

Next steps are still awaited from Angela Raynor, Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government, on how the government will proceed, but the chances of this mine ever happening are increasing very slim.

This drone footage shot on 06 April 2023 shows plainly the local environmental impact of the Glan Lash opencast coal mine (dormant since 2019), and sends a powerful message to Carmarthenshire's Councillors, expected to make a decision in the coming months on whether to allow this local environmental travesty to expand in size and continue for longer. See our analysis of the application. Restoring the site will provide employment and environmental benefits.

Not resident in Carmarthenshire? Email the Council via our portal, urging them to make the right decision.

Completing our contact form sends your message to Carmarthenshire Counci and us.

Will Councillors reject the application to expand and extend the Glan Lash opencast coal mine, learning from the huge challenges that Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council is having with the illegal Ffos-y-fran opencast coal mine?

Put into your own words why you want Carmarthenshire Planning Committee to reject the application - here's some points you might choose to include:

Note - a decision may not be made for up to a year or more from now (October 2024)

Wrth gwbhau ein ffurflen cyswllt mae eich neges yn cael ei anfon i bob un o’r 17 Cynghorydd ar y Pwyllgor Cynllunio Sir Gâr, Cyngor, a ni.

Bydd y Cynghoryddion yn gwrthod y gais i ddatblygu ac ymestyn y pwll glo cast agored Glan Lash, dysgu o’r sialensau anferth mae Cyngor Bro Sir Merthyr Tydfil yn cael gyda’r pwll glo cast agored anghyfreithlon Ffos-y-Fran?

Rhowch yng ngheiriau eich hyn pam yr ydych chi eisiau i Pwyllgor Cynllunio Sir Gâr i wrthod y gais - dyma rhai pwyntiau gallwch ddewis i gynnwys:

Bryn Bach Coal Ltd is the coal mining company that operates the Glan Lash opencast coal mine, which has been dormant since planning permission expired in 2019. In 2018, it applied for an extension which was unanimously rejected by planning councillors in 2023. Undeterred, Bryn Bach Coal Ltd is trying again! This time with a slightly smaller extension of some 85,000 tonnes rather than 95,000 tonnes. Check out the company's application and public responses so far.

According to UK Government industrial coal conversion factors, even the reduced Glan Lash coal mine extension could emit over 270,000 tonnes of CO2 from the use of the coal, a further c18,000 tonnes of CO2e in fugitive methane gas from the mine itself, and an uncalculated amount in emissions from years of heavy machinery excavating many thousands of tonnes of coal, soil, and rock, then returning it again.

The CO2e of the methane and coal use alone is roughly the same as driving from the northern most point in Scotland down through the UK to Lands End in Cornwall… 887 THOUSAND times, or dumping 1 in 5 of Welsh households’ recycling for a year into landfill. Bryn Bach Coal Ltd would need to grow 4.8 million tree seedlings for 10 years just to sequester these estimated emissions, which – needless to say – it does not intend to do. Instead, 2.5 hectares of trees will be destroyed, at least some of which is listed ancient woodland. Whatever the company purports about the quality of its coal or who it would sell the coal to, this coal mine extension in a climate crisis is clearly inexcusable, and sends the wrong message nationally, and internationally. The site was originally supposed to be restored before 2018 but extension applications delayed that and resulted in the decline of nationally and internationally protected habitats, and irreversible loss of nature prevented from returning to restored habitats. It’s time to finally return this land to the nature that was uprooted from it over a decade ago, and avoid the mistakes of Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council’s policy of appeasement towards Merthyr (South Wales) Ltd and the Ffos-y-fran opencast coal mine. Beyond the greenwash, this small opencast coal mine proposal contributes neither to the rich heritage of Wales, nor to its green and bright future.

Coal mining has long been a part of Welsh heritage but it would be wrong to suggest that a small 11-person private coal mine has any potential to make a positive contribution to the culture of the area… as over 600 letters from Carmarthenshire residents opposing the mine extension in 2023 indicates. As one South Wales resident said “Coal is our heritage, but it cannot be our future”.

The Glan Lash opencast coal mine was originally granted planning permission in 2012 on the condition that it would be restored by 2018. But an extension was approved by the Council in 2018 to mine until 2019, on the condition that the site would be fully restored by March 2020. But Bryn Bach Coal Ltd tried again to extend its coal mine in 2019, claiming it can’t honour its promise to restore the site until it gets a decision as it’d waste resources to dig up the earth it’d just filled in. Well, it’s application was rejected in 2023…and, over a year later, still no restoration.

Instead, Bryn Bach Coal Ltd is trying again to extend the coal mine, claiming “Due to the compact nature of the mine site only a limited area of progressive restoration will be possible before the completion of coaling.”. The extension would delay restoration yet again, this time by over 5 years. That’s 12 years of delays since restoration was originally promised to be completed by. And history indicates it’s likely Bryn Bach Coal Ltd would apply for yet another extension after this one – will the site ever be restored?

This clearly flies in the face of Wales’ MTAN 2 policy “As a part of any application for extension, the operator is encouraged to demonstrate that this does not delay progressive reclamation of the principal part of the existing site.”. It’s long overdue that Bryn Bach Coal Ltd makes good on its promise to the local community in Ammanford, as well as to the nature it destroyed and displaced in 2012, that it restores the site without further delay and to the agreed standard.

Our understanding is that of the 11 full-time jobs engaged in the coal washery and proposed coal mine extension, only 3 of those jobs would be new jobs. Eight of those jobs, as well as indirect jobs, are not dependent on the proposed coal mine extension, but rather on the washery which has been operating without Glan Lash coal for years. So, in reality just 3 new, time-limited, jobs in a declining industry are supported by the proposed Glan Lash extension – which cannot be considered to make any material ‘positive contribution to the prosperity of Wales’.

Bryn Bach Coal Ltd claims some of the closest residents live some 440 metres east from the centre of the Glanlash Extension Revised site. This is misleading – the closest residents live just 200 metres from the edge of the proposed extension’s void, with hundreds of tonnes of overburden dumped by large machinery within 180 metres of their back gardens. Wales’ MTAN2 policy is clear: “coal working will generally not be acceptable within 500 metres (m) of settlements”.

The closest residents to the existing site appear to live just 30 metres from its boundary, further jeopardising restoration works. MTAN2 policy requires “Strong evidence of the necessity for remediation, including the evaluation of options, is required to justify working within 200 m of a settlement, and the social and environmental impacts on the affected settlement must be carefully weighed.”.

The Marsh Fritillary butterfly is protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and its habitat is protected under the EU Habitats Directive. The butterfly is also a UK & Wales Biodiversity Action Plan Priority Butterfly Species. The proposed destruction of the Marsh Fritillary butterfly habitat to the north of the existing void at Glan Lash was one of the main reasons for rejecting the application to extend the coal mine in 2023. Despite the clear value and urgency given to this species and its habitat, the environmental impact assessment indicates that “During the seven years since the 2017 Marsh Fritillary site condition survey the habitat has received no management and has continued to deteriorate” (p74) under the ownership of Bryn Bach Coal Ltd. Restoration of this site was originally promised to be completed by 2017, but delays due to mining extensions have resulted in this deterioration. It would seem none of the “progressive restoration” described by Bryn Bach Coal Ltd has touched the most ecologically vital part of the site, and throws into question the company’s ecological stewardship and commitment to restoring the site to a high standard.

It could be read that the Bryn Bach Coal Ltd goes on to use the decline it’s overseen of this vital habitat as a bargaining chip to leverage approval of its new extension proposal that excludes this habitat from destruction, with its environmental impact assessment recommending “The early granting of planning permission for the mine extension would allow an early start to the proposed habitat restoration and management scheme which is becoming increasing urgent as time passes.” (p74). The urgency is of Bryn Bach Coal Ltd own negligence, and there is nothing preventing the company from addressing that urgency now. Indeed, its failure to do so until now, there is no reason to disbelieve the company’s claim that “The habitat will…subsequently be managed to maintain the habitat in good condition for the duration of the mining operation” (p6, Green Infrastructure Statement).

Trees can host nesting birds and protected bat-life, as well as be ecologically important in their own right. Therefore a thorough tree-by-tree assessment is needed – but despite proposing to destroy 80% of a woodland, the environmental impact assessment for the proposal admits the a woodland survey is incomplete: “It was not possible to gain access to measure all trees due to bramble or scrub growth around their bases… no bat-roost use of the central scrub woodland was found but it must be noted that direct-observation of these trees during the surveys was restricted by the impossibility of accessing the woodland” (p48, p50, p57).

Bryn Bach Coal Ltd claims the remaining 20% of woodland along the edge of the void will have its roots area fenced off, but this won’t protect the trees, or their roots, from the reduced availability of water resulting from the void excavated nearby.

Hedges are considered to have huge habitat value, providing essential wildlife corridors, and, as such, are protected by law in the UK. Bryn Bach Coal Ltd proposes ripping up over 440 metres of this critical wildlife habitat, admitting “all hedgerows within the application site qualify as Important Hedgerows under the Hedgerow Regulations 1996”. The company claims the hedgerows mechanically ripped out will be “subject to special treatment to permit their re-use during site restoration and, as far as possible” – but with no details of what that treatment is, and just how far that is possible, these claims are met with scepticism.

There is growing awareness, concern, and action around fugitive methane emissions from active and abandoned opencast and deep coal mines around the world. The methane is release from the act of mining, not from the use of the coal later. There is very little mitigation possible against fugitive methane emissions from opencast coal mining. Bryn Bach Coal Ltd, also fail to detail any mitigation measures for emissions from its site operations such as heavy machinery.

‘Monitoring’ or ‘measurement’ does not amount to mitigation, and it would be misleading to list that activity under any heading of mitigation.

There are shortcomings in the proposed replacement habitats, not least that new plantings are not equal to the established habitats and the mature ecosystems those habitats support. Last year, when Bryn Bach Coal Ltd applied to extend Glan Lash opencast coal mine, the Council’s independent ecologist also pointed out that equivalent biodiversity support from a newly planted woodland habitat (assuming it flourishes) will never catch up to that of the destroyed 2.52 Ha woodland habitat, had it not been destroyed – and that it would take 137 years to support for the existing ancient woodland currently supports. That’s because, habitats are living, evolving, and interdependent ecologies that gain richness as they mature. Simply a larger area does not necessarily equate to more habitat for the wildlife it is intended to support.

The idea of ‘replacing’ a habitat, often not even on the same site – but rather a site some distance away and across two roads – ignores that habitats are unique and are not interchangeable and criticisms of bio-diversity offsets. By way of crude analogy; someone who’s always lived in Ammanford would think much is lost if they were forced out of their home and community, told they must never return, and were moved into a flat in Aberystwyth instead.

One of the more fanciful claims within Bryn Bach Coal Ltd’s environmental impact assessment is that the wildlife, like the nationally protected dormice, would be disturbed by mining activity, get out of harm’s way, then navigate half a kilometre around the opencast coal mine, to the Tirydail coal tip restoration area…despite the fact that on page 59 of the same assessment, the report admits that dormice only travel up to a maximum of 250 metres from their nests.

Bryn Bach Coal Ltd claims “…the survey evidence and the records of casual observations indicate that there is no intensive or regular Badger activity within the application site boundary.” (p10, Green Infrastructure Statement) and “No signs of Badger were found during the surveys although the drier land is likely to occasionally be used by foraging animals.” (p4, Ecological Impact Assessment).

Yet, on a single visit in late 2022, a photographer captured fresh badger prints in mud along the very edge of the void at the Glan Lash site, and shared the photo with Coal Action Network at the time. Unless this was an incredible coincidence, it suggests there is regular badger activity into the very centre of the applicant site boundary, and that surveying has been inadequate.

Bryn Bach Coal Ltd claims multiple places that “The loss of the Site’s ecology is temporary” – but there is nothing temporary about the destruction of ancient woodland, hedgerows, and the lives that depend on these habitats. The company’s own environmental impact assessment only claims some of a select few protected species would translocated into an unfamiliar habitat with unknown survival outcomes. This idea of the nature, and lives within it, that will be killed by this extension is somehow ‘temporary’ because at some later point a new habitat will be installed which may host nature in the future is a peculiar fiction.

In 2023, the planning officer claimed that the negative visual impacts of the extension’s operational phase would be mitigated as they are ‘temporary and relatively short term’. Firstly, a period of 6 years may for many not be considered short-term. Secondly, Bryn Bach Coal Ltd could apply again for a further extension when this planning permission has expired, just as the company is doing now. Unless a further extension is ruled out in a binding way, relying solely on the timespan of this extension risks approving an overall period of coal mining that is unlikely to have been approved originally due to the timespan of impacts. The total timeline of mining impacts should therefore be considered, past and future together—rather than each time extension in isolation, or else decision making risks being based on incrementality rather than material planning considerations, balancing the total cost with the total benefit of the application.

Bryn Bach Coal Ltd claims that the coal is “premium” anthracite coal at every opportunity. But ‘premium’ isn’t an industry grade of coal, and the company doesn’t provide any independent mineral analysis to back up that claim. Furthermore, claims of quality often relate to the carbon content of the coal, with higher-carbon coal being considered higher quality. It does not mean that it is in any way environmentally better — in fact, higher carbon coal such as anthracite emits even more CO2 when burned.

Bryn Bach Coal Ltd goes on to purport that none of the coal excavated from Glan Lash would be burned, which is when the majority of CO2 is released. The company originally claimed 50% would be burned, then 25%, and now 0%...is it just saying what the Council wants to hear whilst knowing that planning permission in the UK cannot control who the company sells the coal to, or if it is burned? Once it has planning permission, Bryn Bach Coal Ltd can sell Glan Lash coal to whoever pays the highest price. Even if sufficient non-burn markets do exist for all of the coal mined from an extension to Glan Lash, it must be assumed that in the absence of any restrictions, Bryn Bach Coal Ltd will sell the coal to whichever market pays the highest price for it. Which market that will be in the future cannot be accurately predicted, so the prudence requires that the Council cannot accept the company’s claim that the coal from the Glan Lash extension will not be burned. Where Glan Lash coal is finally used may also be impossible to trace as the coal processing plant opposite the coal mine also processes coal from other coal mines in Wales and beyond.

This creates a problem for approving the application in light of the Finch Vs Surrey Council High Court judgement earlier this year, which found that when deciding a fossil fuel project, a Council must consider the downstream use of that fuel. This recent judgement also bears on the Planning Officer’s 2023 view that run-of-mill coal will be processed in the washery rather than the coal mine void, and is therefore excluded from consideration of the extension application (despite the fact that the washery is adjacent to the coal mine) so dust generated from processing the coal becomes relevant to MTAN2 paragraph 151.

Where non-energy generating industries continue to rely on coal, it is critical that these industries transition to alternatives as the UK’s decarbonisation progress begins to dangerously veer off the necessary trajectory to avoid catastrophic climate change. Feeding an abundance of readily available coal and maintaining the security of supply disincentives companies to invest in research and infrastructure to cut coal out of their processes, instead ‘locking in’ companies’ continued reliance. There are already known anthracite coal alternatives to water filtration such as sand, gravel, pumice stone, iron, aluminium, and manganese. Although some of these alternatives would also have serious localised environmental consequences, not all would – and none would cause the fugitive methane (a potent climate change accelerant) release, which is possibly the most significant difference between using anthracite coal or its alternatives.

To mine coal in the UK, a company requires both a full coal licence issued by the Coal Authority, and full planning permission granted by the Local Planning Authority.

Following an FOI request to the Coal Authority, we found out that the current licence to mine coal at Glan Lash appears to have been issued in 2019, and expire on 10th August 2025. Given the UK Government’s public and uncaveated commitment not to issue any new licences for coal mining, and that Welsh Ministers would subsequently need to approve it if it was issued, it can be assumed that mining at Glan Lash must permanently cease by the date of its current licence, which is incompatible with the 5.4 years of coal mining it’s proposing.

The 2023 planning officer’s report for the original extension proposal at Glan Lash claimed “the proposal would help to ensure that any coal being used from the site will have been won in a way that is conscious of health and safety regulations and worker conditions”. This statement relies on 3 unspoken and unevidenced assumptions:

Each of these assumptions would need to be investigated and evidenced before it is reasserted for the new Glan Lash coal mine extension application by the Planning Officer.